French Design History

A Timeline of Styles from Louis XIII to the Second Empire

French furniture design reflects more than changing tastes — it mirrors the cultural, political, and artistic forces that shaped the country itself. From the restrained geometry of Louis XIII to the imperial grandeur of Napoleon III, this timeline traces the key stylistic movements that defined the decorative arts in France between the 17th and 19th centuries.

Louis XIII

Reign: 1610-1643

During the reign of Louis XIII, French design began to move beyond the strict classical influence of the Renaissance. Furniture became more varied in form – chairs, tables and armoires emerged with clearer typologies, replacing the dominance of the coffer.

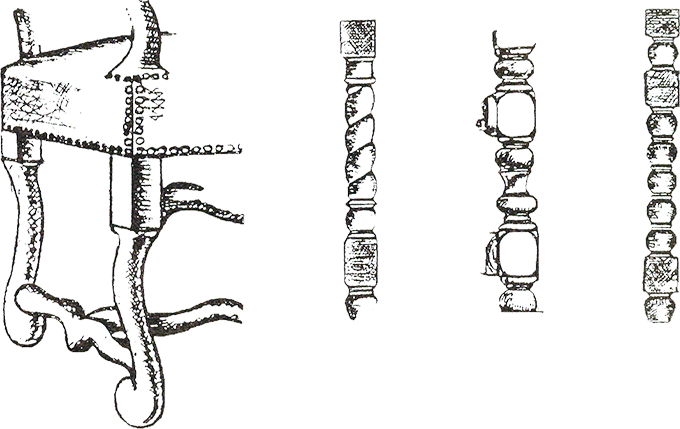

Decoration was more architectural than ornamental. Diamond-point carving and turned wood elements became common, particularly in legs and stretchers. Forms remained substantial and imposing, most often crafted in oak or walnut. The style was sober, formal, and often geometrically inspired.

Louis XIV

Reign: 1643-1715

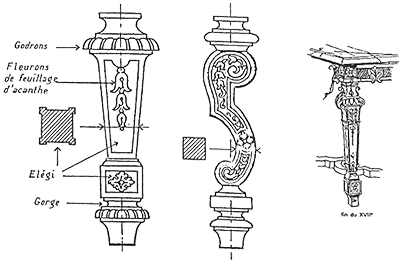

Louis XIV, the “Sun King,” brought France’s decorative arts to new heights through the splendour of Versailles. Furniture of this era was monumental, masculine and rooted in Baroque design principles. Each piece was conceived to harmonise with the architecture of the space.

The commode – a chest of drawers raised on legs – replaced the cassone. Console tables, richly carved and gilded, were placed beneath tall mirrors. Upholstered armchairs, sofas and chaise longues appeared in formal arrangements. Decoration was lavish: sunbursts, mythological figures, trophies, shells, and masks. Gilding, Chinese lacquer panels, and painted finishes were popular. Cabinetmakers such as André-Charles Boulle produced intricate marquetry and inlays in tortoiseshell, brass, and exotic woods.

See our Terminology page for brief explanations of terms such as commode, console, and marquetry.

Régence

Period: 1715-1730

Following the death of Louis XIV, the Regency of Philippe d’Orléans marked a transition from Baroque grandeur to a more refined and fluid style. Known as the Régence, this brief but influential period anticipated the Rococo style that would flourish under Louis XV.

Furniture became more graceful. Shell motifs and palmettes were common. New forms appeared, such as the bureau plat and the commode en tombeau. The fauteuil canné typified the growing attention to comfort. The seeds of a more personal, intimate domestic aesthetic were sown.

See our Terminology page for brief explanations of terms such as bureau plat, commode, and fauteuil.

Louis XV

Reign: 1730-1770

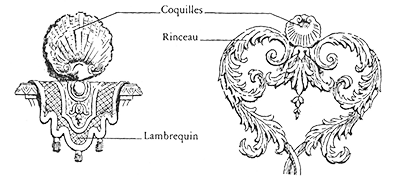

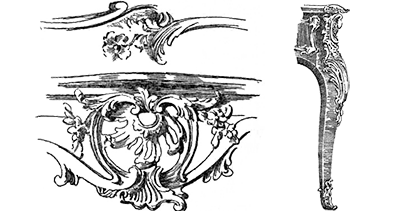

The influence of women at court, and a growing preference for intimacy and comfort, shaped the Rococo style of the Louis XV era. Furniture became smaller in scale, lighter in feel, and far more decorative. Surfaces were enriched with marquetry, painted finishes, and scenes of pastoral life.

Ornamentation was asymmetrical and inspired by nature: flowers, shells, and vines. Cabriole legs and escargot feet became widespread. Tables, writing desks, and dressing tables proliferated, often designed for specific rooms or purposes. Ormolu – gilded bronze mounts – was widely used as a form of luxurious embellishment.

Even provincial furniture adopted the softened Rococo lines, though in simplified form and humbler materials.

See our Terminology page for brief explanations of terms such as cabriole, ormolu, and marquetry.

Transition Style

Circa: 1750-1775

In the mid-18th century, furniture began to evolve again, this time towards a return to classical ideals. The Transition style bridged the decorative flourish of Rococo with the emerging neoclassicism of the Louis XVI period.

Curves became more restrained, and lines began to straighten. Chair frames grew more delicate; backs were often oval or round. Greek key motifs and lozenge patterns emerged, influenced by the archaeological discoveries at Pompeii and Herculaneum. Decoration moved from whimsy to order.

Louis XVI

Reign: 1770-1790

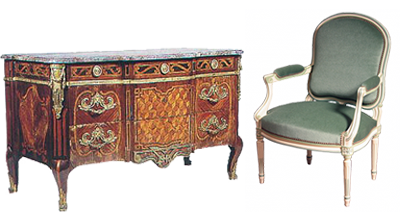

Under Louis XVI, classical ideals fully returned to French furniture. Curves gave way to straight lines and symmetrical proportions. Decorative elements drew from architecture – fluted legs, ribbon-tied garlands, rosettes, and pinecone finials.

Painted finishes were common, and some exceptional pieces featured inset panels of Sèvres porcelain. While neoclassicism dominated Paris, simplified versions of the style were adopted in provincial furniture. The influence of Louis XVI continued into the early 19th century, even as revolutionary politics changed the structure of French society.

Directoire and Consulat

Period: 1790-1805

The Directoire era followed the Revolution and reflected the austerity of its time. Furniture became plainer, echoing Roman rather than Greek classicism. The use of light woods, reduced ornament, and simpler silhouettes aligned with democratic ideals and limited resources.

Under the Consulate, however, national pride and imperial ambition returned to the arts. Neoclassicism persisted, now reinforced by Egyptian motifs following Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt. This “Retour d’Égypte” introduced sphinxes, palm leaves, lion’s paws, and other ancient symbols into the decorative repertoire. Mahogany veneers, gilt mounts, and tapered legs signalled the growing grandeur of what would become the Empire style.

Empire

Period: 1800-1820

The Empire style, established under Napoleon I, expressed a strong, controlled classicism rooted in ancient Greece, Rome, and Egypt. Furniture was architectural in proportion – rectilinear, monumental, and richly veneered in mahogany, rosewood, or ebony.

Decoration was symbolic and bold. Ormolu mounts featured imperial emblems such as eagles, bees, crowns, and laurel wreaths. Large flat surfaces were sparsely carved but lavishly finished. This was the last style in French design history to be created entirely under state direction.

Restauration

Period: 1815-1830

The fall of Napoleon and the Bourbon restoration brought a loosening of strict Empire formality. Known as the Restauration or Charles X style, this era favoured comfort and a slightly more romantic sensibility. Lighter woods were often inlaid with darker accents, and mahogany – increasingly scarce – gave way to native timbers.

Ormolu was used more sparingly. Upholstery gained importance, and eclectic influence began to emerge. Though still neoclassical in foundation, furniture of this era feels less formal and more domestic in character.

Louis Philippe

Reign: 1830-1848

The reign of Louis Philippe coincided with the rise of the French middle class and the advent of mechanised production. Furniture of this era reflects both – it is practical, solid, and designed for comfort, but still finely crafted.

Designers freely borrowed from past styles, resulting in eclectic combinations. Curved forms softened earlier angularity, and veneers were skillfully used to create decorative effects. While not as ornate as Empire furniture, Louis Philippe pieces exhibit elegance through proportion and restraint.

Second Empire

Period: 1855-1880

The Second Empire revived and reinterpreted earlier French styles with vigour and theatricality. Designers, upholsterers, and decorators combined elements from Louis XIV, Louis XVI, Rococo, and even Gothic influences to create richly furnished interiors for a newly affluent class.

Heavy upholstery dominated seating. Dark woods, including ebonised finishes, became fashionable. Boulle-style marquetry reappeared in cabinets and desks, though often with less finesse than their 18th-century predecessors.

This period marked the beginning of a more decorative, layered approach to interior design – one where furniture served not only function and form, but atmosphere.

Understanding the evolution of French furniture is more than a study in style – it is a way to recognise the influences, innovations, and ideals that shaped each piece. As materials, motifs and forms changed across centuries, so too did the role of furniture in daily life. Whether you are drawn to the bold grandeur of the Empire or the quiet elegance of Louis XVI, each era offers its own sense of beauty and intention.